Othello news

Wipe-Outs

11 August 2025Written by Jonathan Cerf

How to Achieve a Wipe-Out Against a Novice or Otherwise Incompetent Opponent

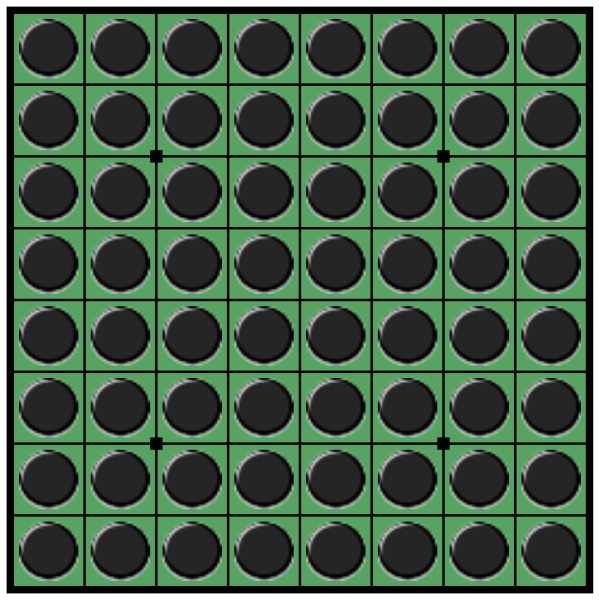

To everything there is a season. There are times to be merciful, to allow your opponent the dignity of a respectable loss. However, those times are rare. Most of the time it is acceptable to throw mercy out the window, and (in the words of Conan the Barbarian) to crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and hear the lamentations of their women. When you are playing Othello, such times call for a complete wipe-out. According to the rules in most tournaments, a wipe-out is usually scored as a 64 - 0 win, even if one or more squares remain vacant in the final board position. However, a wipe-out that leaves the board completely filled with 64 like-colored discs is especially awe-inspiring and especially intimidating. So that's the sort of wipe-out I'll be writing about here.

To have a realistic chance of achieving a wipe-out, you are first-of-all going to need to capture one of the board's four corners very early in the game, probably not much later than the game's twentieth move. You might think that there isn't much you can do to optimize your chances of securing such an early corner. But that's not true. If you are sufficiently confident of your opponent's complete ineptitude, you should consider adopting during the game's opening moves a reckless style of play that offers your opponent as many chances as possible to blunder onto one of the board's so-called "X-squares" (b2, b7, g2, or g7). Shown below is an example of how this can be done. Within a very short span of moves, Black offers White potential access to three of the four X-squares:

Think of Black's moves above as setting traps. Once your opponent has stumbled into one of your traps, and you have secured an early corner, you should immediately change your style of play. No more Mr. Nice Guy. Your next objective should be to accumulate as many "stable" discs as possible in the immediate vicinity of your corner (a "stable" disc is a disc that can never be surrounded and captured by your opponent, even with the most improbable imaginable sequence of moves). Shown below is an example of how discs can be stabilized:

There is a second goal you should keep in mind while stabilizing discs. Notice in the diagrams above that Black is in complete control of the game. Whenever it is White's turn to play, White has very few options. And with careful planning, Black can ensure that White will have very few options (and quite often no options whatsoever) for the remainder of this game. Black is essentially playing solitaire from this point onward, and that's very desirable.

As you accumulate stable discs, try to think two or more moves ahead, much as you would try to do when playing a normal game. And ask yourself, "Will any of my opponent's discs be particularly difficult for me to flip?" If so, make a plan for how you will get at them. Remember that if you allow even one of your opponent's discs to become permanently unflippable, any chance you might have had to achieve a wipe-out will be gone.

Even if most of the discs you are stabilizing are easy-to-get-at discs, try always to think carefully about what new options, if any, you will be creating along the way for your opponent. Keep in mind that you will absolutely need and WANT to give your opponent occasional opportunities to move. For instance, in every single one of the illustrations above, there is no way that Black can immediately occupy corner square h1. To do so, Black will need a white disc on one of the squares immediately adjacent to that corner (at g1 or g2 or h2). So, yes, you will need to sometimes allow your opponent to place a new disc on the board, but you should always do so with great care, insofar as possible offering your opponent only moves that will be advantageous for you. Shown below is an example of what I'm talking about:

The three diagrams immediately above do more than illustrate how you can benefit from giving your opponent an opportunity to play. They also show what sort of near-final position you should aim for as an intermediate goal while you work toward completely wiping out your opponent. A slightly cleaner (and easier to remember) version of this near-final position is shown in Diagram 19 below.

Actually, you should be aiming for something similar to this, but not exactly like this, because while Diagram 19 provides an image that is easy to keep in mind, perfection here is neither required nor is it even desirable. In fact, while it would be easy for Black to capture all of the white discs in Diagram 19, it would not be possible for Black to completely fill the board with black discs. And here is why: To fill the board with black discs, Black would need to place eight new black discs on the board, making eight separate moves. Every one of those eight moves must (according to the rules of the game) capture at least one white disc. But whatever move Black makes first would capture at least two white discs, leaving behind no more than six white discs, too few to allow Black to make the necessary additional seven moves, even if Black picks off those six white discs just one at a time.

A successful continuation for Black after the position shown in Diagram 21 above can be found below in the transcript for SAMPLE GAME #1. I played all six of the sample games below against a wonderfully inept computer program that I found online at https://othello-rust.web.app/#game-over. I think you will gain more insights about wipe-outs from these sample games than you will derive from any further advice I could offer you. I was unable to find a way to play as White against this computer program, so all of the wipe-outs shown below are for Black. After several games, I discovered that the program's "level of difficulty" is adjustable. But I was pleased to find that the program played every bit as idiotically at its highest level of difficulty as it had played at its out-of-the-box level of difficulty. In its favor, the program does not always make exactly the same move when presented with identical situations. For instance, sometimes it will play the diagonal opening, sometimes the perpendicular, and sometimes the parallel opening. This makes it a more interesting and more entertaining repeat adversary. Whenever you feel that you have a sufficient grasp of wipe-out tactics to give achieving your own wipe-out a try, you're going to need an incompetent sparring partner to help you practice and hone your skills. In that regard, I don't see how you could do much better than to play against the same program I used to create the following sample games:

At this point, you might be thinking, "This is all well and good, but I am unlikely ever to encounter a human opponent either ill-informed or stupid enough to make an early unprovoked move to an X-square." My own experience strongly suggests that's simply not true. They're out there, I promise you. But even so, to achieve your own complete wipe-out, you will need a lot of skill, a lot of practice, and a surprising amount of luck (your incompetent opponent's moves may often be arbitrary, but just because they are arbitrary, doesn't mean they will always be pleasingly bad). Do not get discouraged if on your first several attempts, you are unable to achieve anything approaching a complete wipe-out. There is a reason that wipe-outs are so very rare (even in informal games), and the reason is that they are very difficult to accomplish. Mastering all the skills you'll need to completely wipe-out an opponent will be hard work, but I think you'll find that the payoff is out of this world. After all, what could be more fun than crushing your enemies, and seeing them driven before you?